Reviews

Contemplative Play

by Shana Dumont-Garr, 2015

Gerry Perrino’s paintings and prints locate us in familiar yet surreal interior landscapes. They

offer a point of view that we rarely allow ourselves. Rather than the vague periphery, a host of

keepsakes and toys stand in still and symmetrical compositions with precise rendering and

clean lines. Typically, such objects mark memories and entertain us, but these scenes contain

unexpected connections. As arrayed in Perrino’s Vignette Vernacular series, the objects

reference current and historical events, longstanding cultural misunderstandings, and universal

human frailties. The artist frames the scenes so that our reactions may teeter on a seesaw of

humor and paradox.

Each intimate environment centers on small objects so that they take on larger and at times

monumental scales. Luck of the Irish depicts a dignified portrait bust of John F. Kennedy gazing

into the middle distance, his life and death dates displayed on the base. A smaller scaled

statuette of Richard Nixon stands nearby, facing Kennedy in apparent contemplation. The

placement of each object, compounded by the title, raises a host of associations regarding the

two U.S. presidents.

Throughout this body of work, people do not appear, prompting the question of who made

these scenes? Was it a child, and if so, was it accidental, or did a level of understanding inform

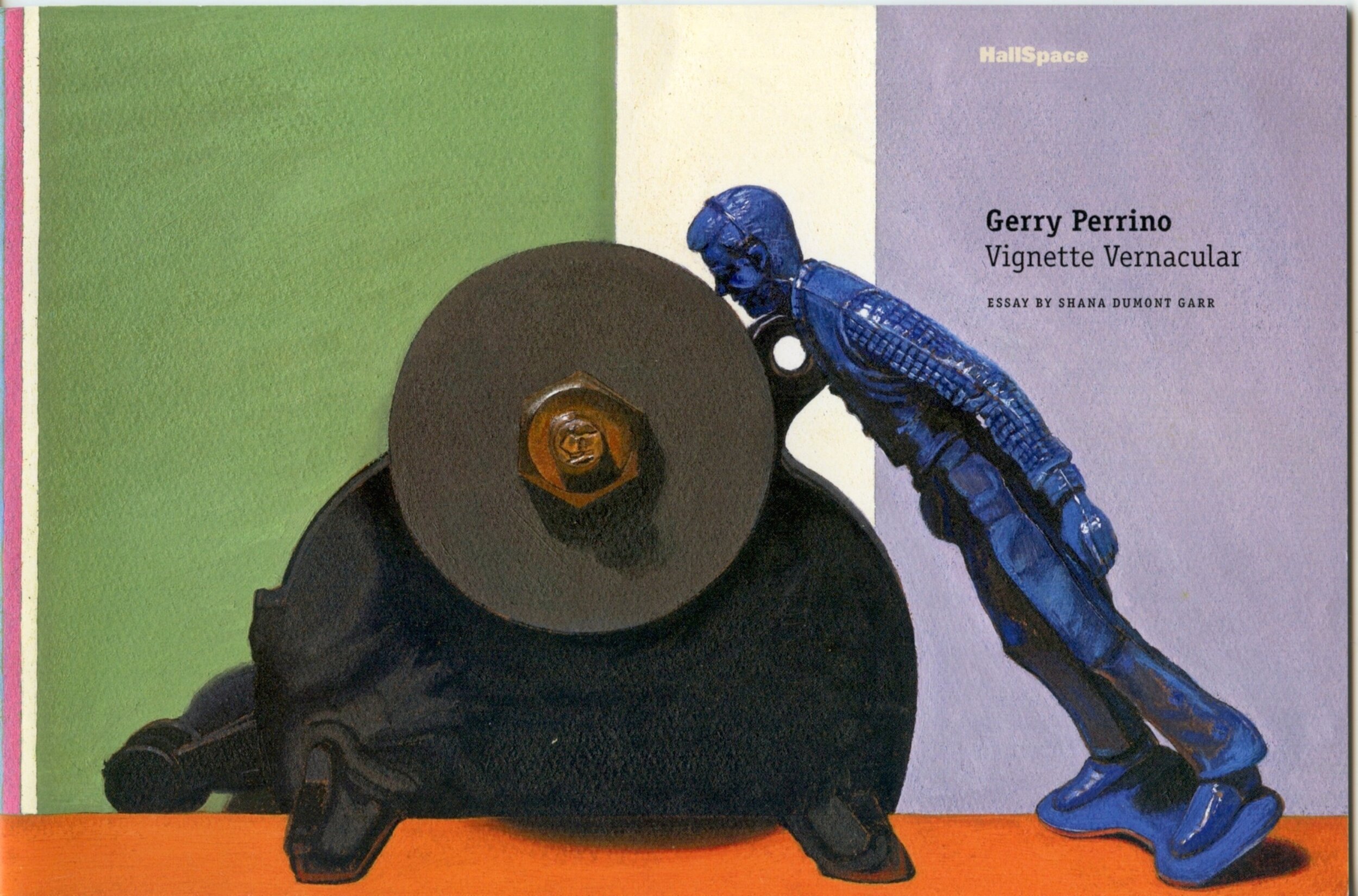

her or his play? Each image keeps us guessing. A blue figurine leans on the edge of a grinding

wheel in It’s a Grind: Still Life with Grinding Wheel and Toy. The seam of the mold the made

the plastic toy is visible and the man’s casual pose appears oddly stiff because he is propped

forward, yet we empathize with his plight as he literally keeps his nose to the grindstone.

Perrino enhances his images with word play as a means to consider the importance or context

to interpretation.

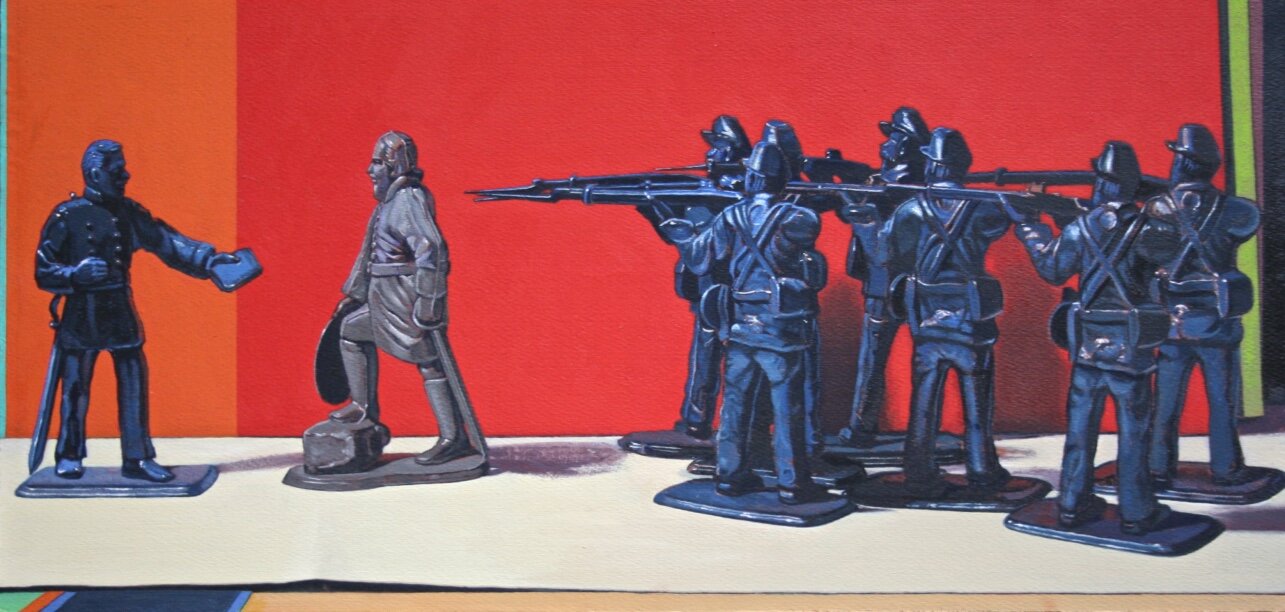

Sacred things may appear silly, depending on how they are introduced. In Desecration, three

figures hold rifles and gaze at a Buddha statue, and one of the men aims his rifle toward the

Buddha’s groin. In Je Suis Charlie, a French maid in a scanty, cleavage baring costume leans

forward, her neck exposed to a sword-baring figure dressed in 19-century Islamic garb. In a

case of life being stranger than fiction, Perrino actually created Je Suis Charlie before the

attack at the Charlie Hebdo offices in Paris in January of 2015, and he was just putting the

finishing touches on the piece as he heard about the gunman. The figure’s dated clothing in

the image reminds us of the longstanding tensions between French and Muslim cultures.

If only opposing viewpoints such as theirs could be resolved by upending the standoff with

the flick of a finger, or by rearranging a shelf. In these scenes, the viewer is a giant at play,

with a God-like perspective of the objects, suggesting the potential for us to come closer

to an understanding, of at least a recognition, of ourselves.

Gerry Perrino:

Vignette Vernacular

Cate McQuaid- Boston Globe, December 31, 2015

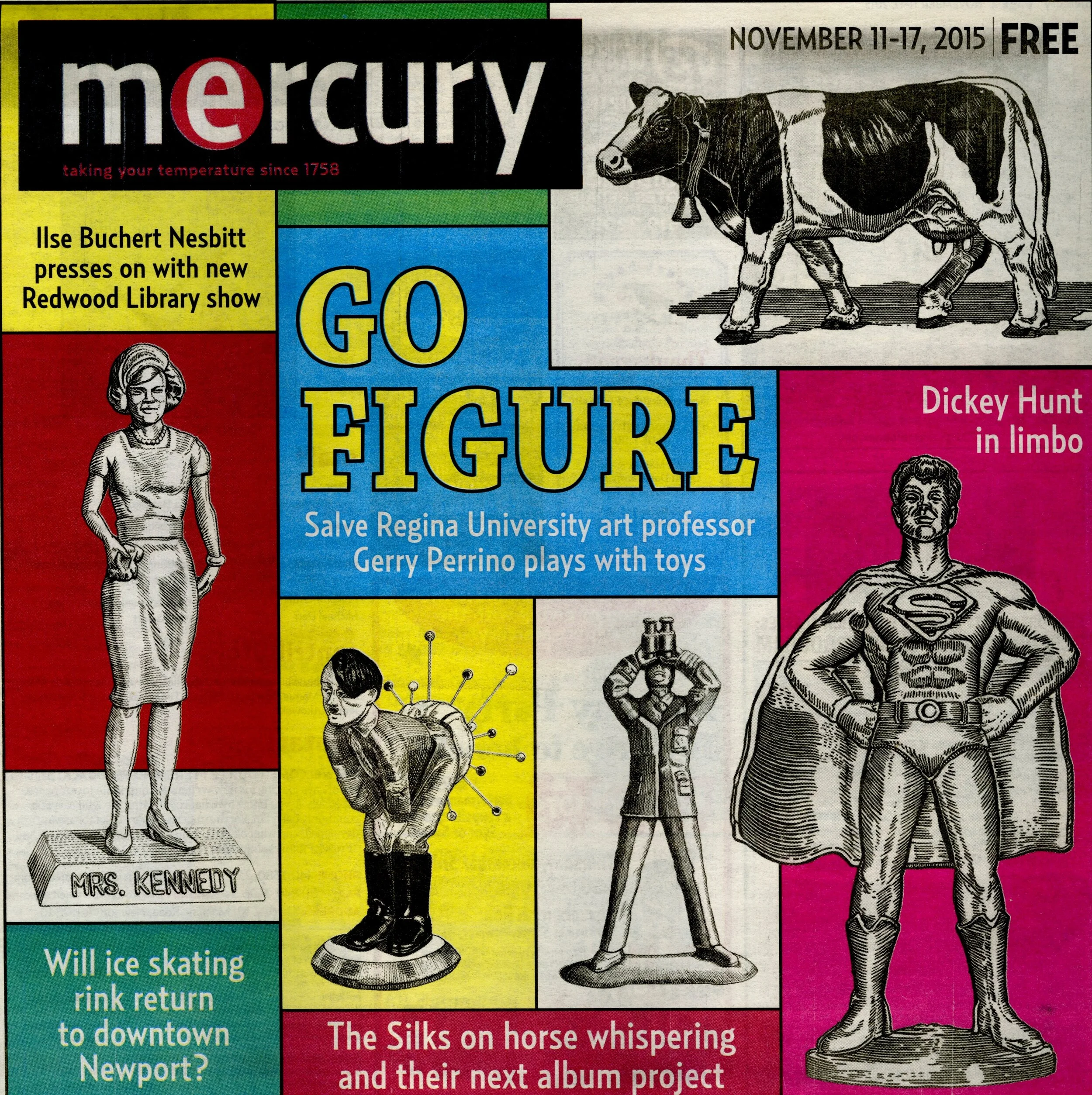

Go Figure

: Salve Regina University art professor Gerry Perrino plays with toys

By Alexander Castro for Mercury,

November 11-17, 2015

It started with a barbarian. Gerry Perrino knew he wanted to make art, though he wasn’t too sure as to what exactly, so he headed to art school with a solitary image impressed on his brain: Conan the Barbarian. But Perrino struggled with figurative work. Eleven courses in figure drawing eventually erased his discomfort with the genre, though he seldom used those skills.

When a health problem pushed Perrino toward working small, the human body re- emerged—not in the flesh, but in technicolor plastic. He began painting toys. “After all those years, I found a way to get the figure back into my work,” Perrino said. That statement is true on several levels for Perrino’s “Graphic Work,” opening Thursday, Nov. 12, with a 5 p.m. reception at Salve Regina University’s Dorrance H. Hamilton Gallery. This latest development in Perrino’s hybridized still life contains the human figure in figurine form. Baby Boomers will be familiar with the cast of Perrino’s inked drawings and linocut prints: JFK, RFK, Nixon. “Using toys instead of just objects revolutionized my work. They have an appeal,” says Perrino, as associate professor of art at Salve Regina. “You could have the world’s most mediocre figure painting next to the world’s greatest still life and people are going to pay just as much attention to that mediocre figure painting.”

The toys first appeared as oil painting s in “Shelf Life,” Perrino’s 2013 exhibition at Newport Art Museum. The artist grouped together soldiers, bikini-clad women, cows, businessmen and politicians in open-ended narratives. In “The Hunter,” it’s uncertain who is predator and who is prey: the black bear of the armed woodsman a foot in front of him. Even slight rearrangement of the toys could produce entirely different stories. “The symbolism is fleeting, “It’s kinda transient, and it’s based upon the context, or even syntax, the order in which you see it.” Perrino said.

The paintings, however, were limited by time and technique. Precisely rendering the toys on tiny canvases became “frustrating” and “laborious.” Perrino’s ideas outpaced the speed of oil paint. He turned to printmaking, and began slicing into sheets of linoleum. The linocuts are more elastic in their storytelling. Perrino can reprint and reposition the figures as needed. “It’s a pretty cheap process. It’s one of the reasons we wanted to teach this [at Salve],” Perrino said. Prints are more salable than paintings. “I want my students to have the opportunity to make a living.” This exhibit will coincide with Salve establishing a “dedicated space and course for printmaking.” The printmaking process recalls the mass reproduction of images and consequently, pop art. But where early pop art grew out of abstract expressionism, Perrino arrived at this distinctive version through realism. You can’t paint realistically, that’s what I was being told…it didn’t matter to me…I have things I wanna say and I can’t say them with abstraction,” Perrino said.

As indicated by his pen and ink drawings, Perrino is a superb draftsman. Black and white is unforgiving territory, a realm where unconfident lines are quickly exposed, but Perrino has nothing to fear. His sketchbooks, populated with portraits of toys, are impeccably clean. Still, he misses the vibrance of oil paint. He’ll continue making prints, as they dovetail nicely with his working schedule, but wants to introduce color into the process. “as an artist, you figure out what you can get done in the time that you have,” Perrino said.

His art maintains a blunted reverence toward pop cultural symbols. Perrino obviously enjoys the whimsy inherent to toys—especially the somewhat bizarre crossover between politics and and plastic seen in presidential figurines. A “big fan” of Freud, Perrino uses playthings to hint at the darker meanings these mass-produced objects might portend. “My paintings are [often] not pleasant,” Perrino said. “They’re about murder, mayhem, rape, objectification.” Humor “soften[s] the blow” of the serious messages he relays. Perrino’s paintings are a tad grimmer than the prints that comprise the “Graphic Work.” His current pairings rely more on sequence than space. The farmer woman was one of my favorite “cast members” in Perrino’s work. In “Poser” she looks, unimpressed, at a showboating Superman. In his “Working Girls,” she’s teamed with a reclining nude woman, making for a subtle and effective comment on the physicality of so-called ‘women’s work.’ Toys are important. They elicit and amusement and wonder, perhaps most concentrated in children, that activates the senses. They are also crassly commercial things, often manufactured with the intent to reap the childish awe for profit. And for adults? Toys are loaded with the sweet gunpowder of nostalgia. Perrino exposes their symbolic character with a quiet bang.

A Shelf Life : Toys in the Attic

by Ernest Jolicoeur 2013

At the top of the stairs lies an angular attic workspace surrounded by shelves. But in this tightly packed wooden room mismatched shelving functions more like a stage set than a storage system. It serves as an organizing principle and a testing area for a studio that’s brimming with dioramas and still life compositions. This is the center of Gerry Perrino’s invented world, his personal playground for collecting, model making and painting. Over the last twenty years Perrino has mined the material world for memorabilia rich in metaphoric content. From miniatures and toys to antique hardware and tools, he’s collected a wide array of artifacts that embody a sense of history and tease the imagination.

For his first museum show the painter recasts an assortment of figurines, photographs and colored papers to explore some of the social and political struggles of his lifetime. Perrino was born in 1957 and his imagery reflects the influence of his formative years. It’s suggestive of a young boy growing up around toys and television, learning about the world from nightly newscasts. The second half of the twentieth century was a period of unprecedented advancement in American culture.

But it’s the social inequalities and abuses of power the artist witnessed that he revisits in this new work. He typically develops each painting around a fundamental theme like truth and fiction, good and evil or us and them. Presidents Kennedy and Nixon make guest appearances. They costar with monochromatic military personnel, women in vintage swimwear, foreign aggressors and businessmen in suits and ties.

In many of these paintings, toy props and tiny accessories are emphasized as an interface between characters. Small-scale mirrors, television cameras and weaponry of all kinds play recurring roles in these scenarios. After all, they are the tools of reflection and intimidation that have influenced the course of history.

Perrino repeatedly appropriates imagery from art history and pop culture to locate his study of human behavior in a visual context. Over and over, he repurposes the saturated color fields and vertical stripes associated with modernist painting as a curtain-like motif. With this move he reduces abstraction to a symbol of its idealistic self and transforms it into a theatrical backdrop for depictions of violence and injustice.

In some cases he makes paintings of photographs to deliver a more impactful narrative. This happens in the paintings Desire and Denial (Still Life with Toy and Photo) and Venus (Still Life with Toy and Photo). In both of these images a standing female figure contemplates a photograph of a single oversized object. Through the rendering of a towering ice cream sundae or a colossal fertility figure, the painter confronts the emphasis society places on appearances and he points to the anxieties shared by many young women.

But beyond the serious tenor of his subject matter, there lies an underlying wit. A distinct sense of humor is particularly evident in the naming of individual paintings. Each piece boasts a two-part title that adds both irony and accuracy to a sequence of events. In all cases wordplay accompanies a literal explanation of each still life arrangement. For example, a painting of a female figure that prominently features a camera’s lens and a handgun is titled Shooting Victim (Still Life with 3 Toys). Another depicting a large black bear in pursuit of a much smaller rifleman is titled The Hunter (Still Life with 2 Toys). With this image it’s difficult to distinguish the hunter from the hunted.

In this recent work Gerry Perrino showcases both his extraordinary skill as a painter and his love of storytelling. Verisimilitude remains his vehicle. And through his masterful handling of oil paint on small panels his carefully crafted allegories draw us in and reward our reflection.

Ironic Man,

“Shelf Life”: Gerry Perrino

By Amanda Lyn DiSanto, Mercury, January 23-29, 2013

What might parts of our lives, past and present, look like if made of plastic and placed on display? Sometimes we exploit or see each other in stereotypes. And sometimes, painter Gerry Perrino reminds us in a new show at the Newport Art Museum, we deny ourselves happiness. “Shelf Life” is a collection of still life paintings similar in size and shape. With their minimalist backgrounds and vibrant colors, Perrino’s works begin to look like panels from a comic book. As in traditional superhero comics, the characters in these paintings are stereotypes, charges with powerful social meaning but represented ironically. The subjects are any number of “toys”, as the titles describe most of them. Most of these toys are figurines of people in the style of green army men, with action poses and plastic pedestals.

They are painted in monochromatic schemes of red, blue, silver and gold, and they suggest visual narratives with themes of gender roles, politics, war, and power. There’s a feeling that the whole thing is manufactured with a wink or tongue in cheek, each painting’s story part of a meta-narrative engineered by Perrino, an associate art professor and chairman of the Art Department at Salve Regina University.

The viewer’s relationship with the toys feels surprisingly intimate. Who hasn’t looked upon a decadent plate of food and experienced inner conflict? In “Desire and Denial (Still Life with Toy and Photo), a thin, faded-looking toy woman stands with her back to a realistically rendered, larger than life sundae. The Viewer enters this painting mid-story. The woman has already gone through stages of surprise, delight, desire and denial after finding the giant sundae, wanting, and then rejecting it.

“The Censors (Still Life with 3 Toys) is about a larger battle. Three figures, each a primary color, stand around an unlit match as long as they are tall. The first figure is shoveling something, maybe dirt, maybe coal. The second and third figures each wear masks as they are about to spray something hazardous at the match. One has a canister of carbon Dioxide, which will put out a flame. They seem poised to suppress the fire they expect will come from the match. In the world outside the painting, censors extinguish the fires of expression, and in this painting, they are prepared to do so before the fire even starts.

“Shooting Victim (Still Life with 3 Toys)” treats media differently, representing media’s often exploitive nature. In this painting, a naked, monochromatic woman sits facing a gold camera man and film camera. There are more background colors than in other works, but there’s no actual scenery to suggest a story or event. It’s just her body and the camera. Doubling the title’s meaning, a silver-colored man standing behind the woman points a gun at the back of her head.Whether he is coercing her to take part in the film or he is a metaphor for physical or linguistic violence against women, his presence adds a layer to the narrative.

Why use toys to represent all this? Toys are to play with, collect, discard. Perrino’s toys are representations of the human-created stereotypes. We are toys: things played with, then discarded by ourselves and others. But we also have control over these images. We are the ones who reduced the female form, guns and other tools of power to playthings. That means we can also make new toys, melt down the old ones, and use our imaginations in new ways. I believe that Perrino would invite us to do just that.

Everyday beauty and strangeness in Newport still Life exhibit

By Bill Van Siclen, Journal Arts Writer, Providence Journal, March 14, 2013

When was the last time you saw a really good still life, the kind that takes something familiar-a vase of flowers, a plate of food, a bowl of apples – and turns them into something magically new and different? If it’s been a while (and given the generally sorry state of still life painting these days, it has probably been a while) plan on making a visit to the Newport Art Museum which is hosting a small, but excellent exhibit of paintings by the Newport-based still-life specialist, Gerry Perrino.

A Professor at Salve Regina University, Perrino has the gift all good still life painters have- namely, the ability to see both the beauty and strangeness in every day objects. In Perrino’s case, the objects are a collection of plastic toy figures of the sort that you might have found in a child’s toy chest, circa 1960. Among the most popular: a platoon of rifle-wielding GI’s, a gaggle of cowboys and a group of briefcase-carrying businessmen. There are also more exotic figures including a Middle Eastern fighter brandishing a scimitar, a cameraman equipped with an old- fashioned TV camera and a group of buxom young women who look as if they just stepped out of a 1940’s era pinup calendar. By combining these figures in various ways, Perrino is able to conjure up a nearly endless series of visual tableaux-some humorously offbeat, some charges with obvious social and political meanings and some tantalizing in their strangeness and ambiguity.

A painting called “The Intimidating Gesture (Still Life with 2 Toys), for example, is played mainly for laughs, with one of the pinup girls facing off against the fighter with the scimitar. True, the painting may have a political subtext: the young woman, who is scantily dressed and holding a mirror, could represent a clichéd view of the decadent West, just as the scimitar wielding fighter could represent a stereotypical view of an intolerant and violence-prone Middle East. Still, that seems a stretch.

Instead, it’s the sheer incongruity of these two toys-the pinup girl and the holy warrior-that seems to have piqued Perrino’s interest. As for the ‘intimidating gesture” mentioned in the title, it could refer to either the fighter with his sword or the girl with her mirror. Take your pick.

Another painting, “Jubilee,” also features some unusual pairings. In this case, it’s four figures-two, bikini clad young women and two male figures dressed in what appear to be traditional African costumes. Together, they form a conga line that’s as visually lively as it is culturally incongruous. (Then again, a dance historian or musicologist might point out that the connections between African dance music and American popular culture.)

While paintings like “The Intimidating Gesture” and “Jubilee” clearly have an element of oddball humor (even if they hint at deeper meaning), other works are more obviously political. In “Tip of the Spear (Still Life with 10 Toys)”, a platoon of American toy-soldiers rushes toward a lone Arab warrior holding a spear. Sitting directly behind the warrior is a pint-sized barrel of oil. In “Men in Gray Flannel Suits (Still Life with 4 Toys,” meanwhile, our old friend the scimitar-wielding warrior returns-this time to menace a group of well-dressed toy businessmen. In both cases, there’s an obvious reference to contemporary events, even if the specifics remain tantalizingly vague.

Several paintings also demonstrate a fascination with mass media. In “Men Protecting Their Interests”, a TV cameraman films two buxom young female nudes while a group of businessmen looks on. In the background, the tip of a $20 bill can be seen, hinting at the connection between sex, money and celebrity in contemporary media and culture. A work called “9/26/60: In Focus,” meanwhile, features a toy-versus-toy replay of one of the great moments in American media history: the 1960 presidential debate between John F. Kennedy and Richard Nixon. In an interesting twist, the figure representing Kennedy is shown in color, while the figure representing Nixon is shown in monochrome-a possible reference to the debate’s outcome, with the more youthful Kennedy prevailing over the stiffer, stuffier Nixon.

Syntactic Structure at Hallspace

Lacey Daley, Artscope Magazine, January 12, 2012

http://archive.constantcontact.com/fs077/1101530073189/archive/1109034600711.html

Jubilee (Still Life with 4 Toys) by Gerry Perrino, 2010, oil on panel.

Don't be fooled by the commercial appeal of the toys and figurines depicted in this exhibition--they have something much more important to say. With his most recent collection of still lifes, artist Gerry Perrino attempts to engage his audience in metaphoric symbolism and collaborative interpretation. The works in Syntactic Structures, Perrino's solo show comprised of fifty-one paintings, speak to the importance of context and syntax in every situation. To explain, the artist himself uses the following examples: "For instance, given the right conditions concerning context and syntax, a broken hammer could reflect a maimed warrior; a mallet and chisel could be used to imply the Creator; or a running figure might be seen as either heroic or cowardly. The environment in which such objects are placed is the key to establishing metaphoric symbolism within them." These figurines are more than just psychedelic plastics; they are pieces to a larger narrative reflecting on history, current events, life, and society's habits. The most remarkable part of this process for Perrino has been the ability of the figurines to transform each painting, soon enough becoming dominant and necessary parts in the series. "I came to find that the inclusion of figures greatly amplified the expressive potential of the paintings. Inclusion of these elements seems to concentrate the work's thematic focus directly into the area of human relationships," said Perrino. Syntactic Structure is on view now at Hallspace. If you have not had the chance to make a trip into the city, you are in luck. The Gerry Perrino final exhibition day has been extended to Saturday, January 21st. You know the saying about second chances; don't let this one get away. Come give the artist your discussion and personal interpretations--he welcomes it with open arms.

Gallery Notes

, Subject/Object

By Liz Clark, Gallery 800 February 6 to March 7, 2004

Gerry Perrino acknowledges that much of his work is autobiographical, either inspired by his career as a journeyman professor or the love of Catholic ritual learned as an altar boy. For him, the object itself is the subject and does not need the embellishment of grandiose theories. His influences range from the Pop Art of Jasper Johns to the “delicious complexity” of cartoonist Rube Goldberg.

As with many of the elements of his three-dimensional works, he found the telephone in The Academician: Shell Game tangled in the weeds of a long-defunct drive-in theater. The phone without a dial (actually an intercom) sits on a scruffy end table, its cord leading only to a painting of itself. “Sometimes I found myself rambling on about something that wasn’t terribly important, making it a part of something grander instead of just looking at an old idea in a straightforward way,” says Perrino. His now-you-see-it, now-you-don’t shell game is a metaphor for w some overblown, overwrought, and overthought “academese”.

In another piece, A Victim of Its Own Success, a potato is trapped in a Fry-a-lator basket with paintings of the ubiquitous ketchup squeegee and a vinegar bottle framed in hand-carved French fries. Perrino explained that in his years as an adjunct professor, he asked to teach a spectrum of classes at one university, but year after year was offered only one-figure drawing- because, he was told, he did it so well. Later his application for a full-time position was denied because he had never taught advanced classes. He had become the victim of his own success in teaching intro courses.

This show has been seen at the Hallspace Gallery in Boston and at Salve Regina’s University Gallery. His other recent solo shows include the Gardener Building and Po Gallery, both in Providence, and at CC Gallery in Cranston Rhode Island. Recent group exhibits include the Plieades Invitational Exhibition at Plieades Gallery, New York. His work is in the permanent collections of the Boston Public Library, Fidelity Investments Corporate Headquarters in Boston, and the DeCorova Museum in Lincoln Massachusetts, where he lives.

In an Arts Media review of this show, Perrino is lauded for his “wry, intelligent still lifes (that) document the effect of time on objects…all of which present some measure of cheerfulness, beauty, and charm amid seeming disparity and decrepitude.” Perrino agrees with Edward Hopper who said, “If you could say it with words, there would be no reason to paint it.” He would prefer that his viewers draw their own conclusions. He does give clues. “Titles are carefully chosen. I view many of the object/subjects of these pieces as metaphors for the contemporary human condition. My hope is to make the work interesting or intriguing enough that viewers will look long enough to get the grander message.”

A Rhode Island native, Perrino has held teaching jobs there since 1983 at such schools as Salve Regina University, Rhode Island College, and Rhode Island School of Design. From 1999-2001, he was the John Frazer Visiting Artist at Wesleyan University in Middletown, Connecticut. He holds an MFA in painting from Syracuse University.

Subject/Object: Gerry Perrino

Hallspace

By Noemi Gizpenc, Arts Media, June 2003

Many of Gerry Perrino’s wry, intelligent still lifes document the effect of time on objects organic and man-made flotsam and jetsam. One painting, “Happy Birthday” , gathers together a rake head, empty paint tubes, vertebra, handkerchief, crab claw, paint stirring stick, wristwatch, cracked PVC pipe, doorknob backplate, and two ancient clumps of brick tossed into the water and returned years later, worn into soft orangey blobs striped with white mortar.

Instead of “memento mori”, the subjects suggest appreciating the bittersweet beauty of life before and beyond death. Several other pieces use objects for more specific metaphors, as in the potato trapped in a fry basket, “A victim of his own success.” The sculpture “Academician” dryly pokes fun at the hoary and out-of-touch: a phone lacking even a rotary dial sits atop a scuffed end table with a few empty walnut husks below it and a receiver cord that leads only to a life-sized painting of itself.

While weathered tools, rusty car parts, and dusty appliances reside in stately decorum in Perrino’s works, modern technology invades more brashly. The sculpture “Eclipsing the Bard” consists of a small round painting of a bust of William Shakespeare, framed by a nail-and-electric cord crown of thorns, hung on the wall behind a tall, narrow tower-the bard’s head is surpassed by a copper rod topped with a silicon chip. Only one of Perrino’s pieces is called “Three Graces”, but they all present some measure of cheerfulness, beauty and charm amid seeming disparity and decrepitude.

Art Review: Newport show puts R.I. still life in focus

By Channing Gray

Special to The Journal

Providence Journal, posted Aug 3, 2016 at 9:00 PM

There are some imaginative works from a new generation of artists.

NEWPORT, R.I. — The Newport Art Museum’s big still life show is divided into two camps — the old-timers and the new generation of painters such as Shawn Kenney, who takes his inspiration from the old masters to turn out bold, eye-popping paintings of fast food.

And of the two groups, the entries from the current crop of painters are the more rewarding. They’re certainly more imaginative, getting away from vases of flowers and going with more whimsical choices, such as Gerry Perrino’s “Desecration,” in which a toy Buddha with its hand raised in a gesture of peace is surrounded by a group of toy yahoos, rifles pointed.

Maybe I’m growing tired of bumping into John Riedel’s dense, vibrant oils crammed with box tops and tipped-over wine glasses that seem to be everywhere.

But there are two strong pieces from this prolific painter that despite their intricacies, have this attractive raw and primitive feel. “Tide II,” an oil, packs Riedel’s typical repertoire of trinkets around a Tide detergent box, while a somewhat cartoonish “Bach Goldberg Variations III” features among colorful clutter a woman looking like Marie Antoinette playing the harpsichord.

I was immediately attracted, though, to Kenney’s burger, which just jumps off the canvas, oozing with tomato and swimming in a sea of sinful French fries. It’s kind of Poppish, but not cartoonish. Get past the mundane subject matter, and his burger and box of fish and chips are wonderful paintings with lush surfaces and a dramatic use of light and dark.

As for the earlier generation of Rhode Island still life painters, the show starts with John Robinson Frazier, influential head of the RISD painting department in the early 1920s. I knew the name, but had never paid much attention to his work, which is pretty disappointing.

Frazier is credited with bringing about the transition from old studio methods to a more modern approach. But the half-dozen small paintings in this show are pretty crude, with dark, muddy colors. I’d be surprised if they’d made the cut at the Providence Art Club.

But Frazier’s disciple, Gordon Peers, is far more exciting. A couple of oils of apples owe a lot to Cezanne, even though his color range is far more electric.

It is interesting, too, to see the radical transition in the work of Peers’ wife, Florence Leif, a 1934 RISD grad who in the 1940s was painting fastidious, if somewhat quirky, still lifes. Her “Still Life with Horse’s Hoof” features a bony foot in the center of a table covered with sand, with a toy cowboy riding a horse and firing a pistol.

It’s tight, busy with subdued hues. But then Leif and Peers spent time in Europe, where he was head of the RISD honors program, and a decade later, she was painting “Still Life with Fruit,” an intense, almost Cubist piece that’s all about simple shapes and color.

But the canvas that caught my eye was Madeleine Porter’s masterful “Red White and Blue,” an arrangement of plants boiled down to basic shapes, with a wine bottle and a blue polka dot cloth. It’s an arresting image with a distinct voice.

The “Still Life Lives” show is up through Sept. 18. But there is a companion show by Gayle Wells Mandle and daughter Julia Barnes Mandle that’s up through Aug. 9 in the main gallery.

This is art with a message. Gayle Mandle shows her concern with environmental issues such as fracking, oil spills and global warming in explosive black and deep blue abstracts that look like they were made by dropping paint cans on the floor.

In some cases, collage elements are woven into the mix, and there are several glass plates with more blue and black that are supposed to suggest specimen slides of contaminated water.

Daughter Julia, on the other hand, is interested in immigration and has draped a wall with clothing patterns, with a set of battered ceramic suitcases piled in front.

And Newport photographer Thomas Palmer is showing an unremarkable group of photos of Newport’s North End reminiscent of Harry Callahan’s stark shots of Fox Point — alleyways, backyards with shrubs, and lone trees.

But there is a sweet shot of a young couple standing in front of a Sunglass Hut. She is cleaning her glasses on her dress in a somewhat sexy pose, while her boyfriend is smoking a cigarette and lost in his own world.

(401) 277-7492

On Twitter: @Channing_Gray